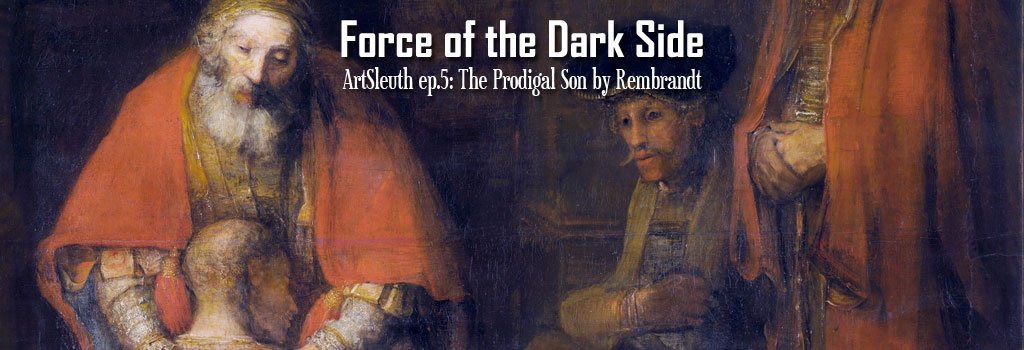

Rembrandt (1606-1669)

The Prodigal Son

Force of the Dark Side (13 min)

2719 views, 1 reviews

Average rating : 10/10

Last reviews

Excellent. A imiter

wonderful analysis!

nothing

I am waiting for : Vélasquez

by

See more reviews

A son gone astray comes home to a loving welcome from his father. Why does Rembrandt choose to obscure the bible story?

Interview with Gary Schwartz

Gary Schwartz is a renowned Rembrandt specialist, author of Rembrandt: His Life, His Paintings and The Rembrandt Book.

CED > “Mystery”, “genius”, “mastery of light and shade”: these are the kinds of thing you often hear when people talk about Rembrandt - but it all seems a bit facile. Suppose I knew nothing about Rembrandt, and this film on his Prodigal Son was my introduction to his work, what advice would you give me on getting through to the essentials? What should I be looking out for?

Gary Schwartz > The use of superlatives is totally appropriate in art appreciation, as is the conviction that certain works can have been produced only by a great genius - after all, we don’t speak of “love of art” for nothing. But we need to be more circumspect in art criticism and art history. From 1890 to 1969, The Man in the Golden Helmet, the first work acquired for the Berlin Gallery with support from its new Friends’ Society, was venerated as one of Rembrandt’s greatest paintings. In 1969, the American art historian Ben Rifkin dared to question its attribution to the master, and its status gradually crumbled in the next 15 years - until the Gallery organised an exhibition to prove to a later generation of Berliners that it was not in fact by Rembrandt. It remained the same object, but public perceptions of it changed significantly. This example alone should be sufficient warning that judgments of quality and genius in art are contingent. Even though they rarely change as dramatically as they did in the case of The Man in the Golden Helmet, they are shifting all the time.

CED > You spoke just now of a “proof” which altered people’s view of an artwork. Surely something like that makes “quality judgments” less contingent?

GS > To be frank, I don’t think that the arguments and evidence put forward in the 1986 Berlin exhibition were as conclusive as the Gallery thought. It wanted to demonstrate its respect for the truth - but may have slightly exaggerated the truth value of the “demonstration”. My own philosophy is that truth exists, but exists in such overlapping, complex and dynamic forms that we can’t pin it down. From the human perspective, everything is contingent, although some things are more contingent than others. For example, the value system that honors Rembrandt as a great artist has remained fairly constant, while the works for which he was - and is - esteemed are changing all the time.

CED > The first thing we might consider, in the case of The Prodigal Son, is the problem raised by the parable itself, in which the Prodigal’s return is celebrated more than the good son’s loyalty. This may be a kind of “religious pragmatism” - a sense that converting is more important than preaching to the converted - or it may be making the point that God’s love is unconditional. What are we to make of Rembrandt’s interest in this Bible story, and the twist he gives it? Is he trying, as a good Protestant, to give the loving father the kind of significance the Virgin has for Catholics? Or is he identifying with the son, as the Dresden self-portrait as the Prodigal - and the fact that he never sold this picture - might suggest?

GS > This is an important point, and no one - not even me, I’m afraid, in my own book – seems to have noted that The Prodigal Son links back to the Kassel Rembrandt, Jacob Blessing the Sons of Joseph. In both, the younger son is receiving a blessing which should go to the older. In the Joseph story, Jacob is giving his younger grandson, Ephraim, the blessing which by rights belongs to Manasseh. Disinheritance is the theme in both, and rightful heirs are passed over by a patriarch.

In Genesis 48, Jacob’s behaviour, like the father’s in the parable, offends, not Manasseh, but Joseph, his father. The text could not be plainer: "When Joseph saw that his father laid his right hand upon the head of Ephraim, it displeased him; and he took his father's hand, to remove it from Ephraim's head to Manasseh's head" (48:17). It strikes me as extremely significant, and by no means fortuitous, that here, as in The Return of the Prodigal Son, Rembrandt leaves out the anger. While Guercino, one of his contemporaries, gives us a furious Joseph, nearly grappling with his father, Rembrandt's Joseph makes the gentlest of corrective gestures and smiles as he makes it.

Can this be linked to Rembrandt’s personality? I am fully aware that proof is impossible, but allow me to propose a theory. Rembrandt was himself a younger son, the ninth of ten children. He did not take over the family business and, although his parents did not disinherit him, his older sister and wife certainly cut him out of their wills. Indeed, Saskia’s leaving of her property to Titus created a situation which led to Rembrandt's financial downfall.

My speculation would go like this: in the biblical pictures we are discussing, Rembrandt identifies with the younger sons, who are preferred to the older ones. He sees himself as receiving the favor and fortune he had forfeited in real life. As you point out, he had actually painted himself, at an earlier stage, as the younger, prodigal son, rejoicing in his debauchery. Personal ruin left him wishing that the effects of that life-choice could be undone, as they are in the parable.

In re-creating the two scenes, Rembrandt gives the disadvantaged or offended members of the family no chance to express their anger. Joseph, his wife and Manasseh in the one painting, and the older brother in the other, are passive and show little reaction. As the artist sees them – no, fashions them – they witness their own diminution in favor of the younger son, and accept it.

Ideas like these may have have been subconsciously active in Rembrandt’s mind. On a conscious level, and as an interpreter of Protestant Christianity, he may well have been harboring, too, the theological interpretation you propose.

CED > The film sees The Prodigal Son as a deliberate attempt to obscure the Bible story, making the message less clear, but the picture itself more mysterious and universal. Of course, other artists do this too - but does it hold the key to Rembrandt’s personal aesthetic? Is a consistent “obscuring” strategy identifiable in the rest of his output? Is there a link between the Prodigal Son and other “obscured” religious subjects, e.g. the various states of his engravings of the Passion ?

GS > It can’t be denied that a fairly large number of Rembrandt’s compositions elude precise iconographical identification. This starts with one of his first major history paintings, which has been interpreted in some 20 different ways, and is now called - in sheer desperation - The Leiden History Painting. In the same way, his Andromeda is the only painting of that subject with no Perseus, and his Danae has no shower of gold. In the Hermitage, another painting is clearly a reconciliation scene, but are the two embracing men David and Jonathan, David and Absalom or David and Mephibosheth ? And who are the man and woman in the painting called The Jewish bride? In my 1984 book on Rembrandt, I suggested alternative subjects for these paintings, none of which has – yet – been accepted by my colleagues.

Sometimes, too, Rembrandt does not omit attributes, but adds them. In one of his Presentation in the Temple etchings (version a), the prophetess Anna is accompanied by a flight of, presumably, sacred doves. The Bible story of Jacob and the sons of Joseph makes no mention of Joseph’s wife, but Rembrandt puts her in. In the St. Petersburg Prodigal Son, he leaves the identity of the secondary figures unspecified.

I do not believe that Rembrandt was aiming at obscurity, but at associations outside the standard iconographic code. Perhaps he meant to create a bit of pedagogic confusion, and so force the viewer to think again about the subject. If so, it doesn’t always work.

CED > More generally, the film suggests that Rembrandt’s religious pictures court the market by combining two types of theatrical effect. One sets out to maximise impact on the viewers, and derives indirectly from Caravaggio. The other is closer to street theatre, and puts the religious action in a contemporary setting, involving the viewers and making them part of the scene. Do you accept this reading - and can we take it further?

GS > Svetlana Alpers has given us an enticing and convincing picture of Rembrandt’s studio as a theatre (book review), where parts are acted out by pupils, sets and models are deployed, and stories are brought to life as they are committed to paper and panel. This is a matter of professional technique with a highly personal edge, like the Stanislavski method in acting. This view of Rembrandt’s teaching practice is borne out by the few notes to pupils he scribbled on drawings, which are mostly concerned with the story - the action.

As for pleasing the market, Rembrandt never went out out of his way to create a sense of drama. Indeed, the work he produced in the 1650s and ‘60s, when he most needed sales, is noticeably restrained.

The Prodigal Son is the subject of a book-length exercise in reader/viewer participation – The return of the prodigal son : a story of homecoming (1992) – by the Dutch-born priest Henri Nouwen (1932-96), who enters the mind and feelings of each of the characters in the parable and figures in the painting, and asks penetrating, unsparing questions about the emotions, behavior and interests of all of them. He links his analysis to his own life and his own relationship with God, putting even harder questions to himself. His approach is the reverse of the historian’s: instead of trying to project himself back into the 17th century, like the historian, he tries to bring Rembrandt’s creation into the present - not the journalist’s political present, but the viewer’s deeply personal, psychological present. I myself am committed to the historical approach, but I also have great respect for this use of Rembrandt. It creates a middle ground on which we can all meet Rembrandt and the figures in his paintings on terms that demand, not erudition, but introspection, concentration and painful honesty. This is close to what Rembrandt was doing when he conceived his religious art. Why not do it ourselves ?

One thing I cannot go along with, however, is denial of the difference between history and introspection. Some authors conflate their own reactions to Rembrandt with historical reconstructions, and claim that the results are historically valid. At this I balk.

CED > The film doesn’t really say anything about Rembrandt’s brushwork and use of colour, which are strikingly different from those of Caravaggio or his Utrecht imitators. What are your views on this?

GS >

Gerrit van Honthorst, le Fils prodigue (1623), Munich

It’s true that Rembrandt was seen in his time as the Dutch Caravaggio, but the comparison had nothing to do with color or brushwork. Both men were regarded as artists who had turned their backs on tradition and worked only from nature. This is, of course, a misconception - but many admirers of both cling to their bad-boy reputations, and so it will not go away. As far as Dutch borrowings from Italian art go, it is well to recall that these were largely filtered through black-and-white engravings - which seemed to bother no one - and that colour was supplied at the receiving end. The light and dark contrasts in the work of Rembrandt and Caravaggio are comparable, but Rembrandt found his own solutions to the problems of chiaroscuro.

It’s too easy to contrast Rembrandt’s work with that of the Utrecht Caravaggists, as if they represented opposing principles. In his early years, Rembrandt’s path repeatedly crossed theirs, and he sometimes emulated artists like Gerrit van Honthorst. As I see it, the differences between them, as between all European artists of the time, were marginal rather than essential. Sometimes these differences were a factor in judging the nature and quality of an artist’s work, but usually they weren’t. I try to avoid latter-day categories in looking at the art of the past.

CED > Your own work has helped to correct the old vision of Rembrandt, and suggest that he was less a humanist mystic, cloistered in his dark studio, than a pleasure-loving, wheeler-dealing and not over-cultivated high roller - which would certainly seem to explain his identifying with the prodigal son. More generally, how have your discoveries affected the way we see his work? Does seeing his life in a new light alter our aesthetic assessment of his paintings?

GS > Excuse me for correcting your question, but I do not see Rembrandt as either sybarite, wheeler-dealer or high roller. I believe Houbraken when he says that Rembrandt was fanatical about his work, and happy to stick with it well into the evening, with only a herring and piece of bread to keep him going. True, he has been accused of money-grubbing, but that was already being said in his own day. It did not take my research to prove that. In any case, I do not really agree. He was irresponsible with money, but the trouble was his passion for collecting - not gambling.

There are three personal traits, where I feel that my work has changed my fellow specialists’ picture of Rembrandt - and gradually the public’s as well. He was capable of great personal cruelty, witness his treatment of his mistress, Geertge Dircx; he was a hard man to deal with and almost always unwilling to compromise, hence the legal battles in which he was constantly embroiled; and he was no friend of the Jews, but a typical Christian of his time, and so hostile to Judaism. Demythologizing him on these few points makes him less humanitarian, but fills out his humanity.

Thinking later about his intransigence, it occurred to me that this psychological feature, which damaged his relations - especially his financial relations - with others, may have been a blessing for his art. After all, we don’t expect great artists to compromise their genius - do we?

CED > Is there any aspect of Rembrandt which is missing from The Prodigal Son?

GS > If there is, it doesn’t matter. The Prodigal Son’s greatest single quality - the one that outweighs all others and overwhelms the viewer - is its almost unbearably poignant evocation of acceptance and forgiveness. If we had abandoned our own father, we would surely yearn for his unconditional acceptance, and complete forgiveness of our shortcomings and wrongdoings. These are things real life cannot give us - but Rembrandt does.

Discussions

Discussion for : ArtSleuth 5: The Prodigal Son by Rembrandt

Discussions allow you to react to the video in an informal way : complement the video with new insights, express yourself and share your opinion. If you want to post a more formal review of the video itself, please submit a review in the "Review" tab.

Donation campaign

Help the production and distribution of this new series of videos More information.

Objective:

20000 €

Money collected: 50€ (0.3%)

Donate now

Donate with a check Latest donors

Credits

Scripted and directed by

Erwan Bomstein-Erb

Rémy Diaz

Scientific expertise

Jan Blanc

Production

Erwan Bomstein-Erb

Rémy Diaz

English translation

Vincent Nash

Voiceover

Erwan Bomstein-Erb (français)

Mark Jane (anglais)

Motion graphics

Christopher Montel

Sound

Arnaud Prudon

Music

Rémy Diaz

Want to work with us ?

Do you speak french ?

Do you speak french ?